2 Research Paradigms and Methodologies for Pedagogical Research

Janice Miller-Young

Introduction

All research begins with a question, problem, or topic of interest. The process of transforming broad classroom issues and interests into precise SoTL research questions is an iterative and reflective process. It involves a thorough literature review, a deep understanding of context, and careful consideration of personal interests, experiences, and available resources. In other words, it can be a complex process, and sometimes it is hard to know where to begin. Before writing a research question, it can be helpful to step back and familiarize yourself with the range of types of research questions that can be asked—in other words, to think in terms of paradigms and methodologies. When researching educational technology in a SoTL context, these foundational concepts will not only help you explore and reflect on different types of research questions but also help you maintain the focus of your research on teaching and learning, rather than on the technology itself. While it is not (yet) common for SoTL researchers to state their paradigm or methodology explicitly (Divan et al., 2017; Haigh & Withell, 2020), we strongly recommend it in this book because it will also help you to a) build a well-designed study and b) increase the impact of your work. Also, many funders and journals require it because it helps you c) better communicate your study to a multidisciplinary audience. This chapter aims to offer a concise introduction to common educational research paradigms and methodologies that are useful for SoTL research.

As an instructor trained in a particular discipline or profession, you hold underlying philosophies and theories about knowledge and how it is constructed—which you may or may not have thought about explicitly, depending on your discipline. For example, in high consensus fields, such as natural sciences and engineering, knowledge is generally seen as accumulating over time—with new studies building on previous ones and branching out into new layers of detail and complexity, like the branches of a tree (Becher & Trowler, 2001). This perspective makes sense for studying the natural world, which most researchers would describe as existing independently of us as humans (although this can still be debated, even in physics!). Researchers from high consensus fields therefore tend to have less experience articulating their philosophies about the nature of knowledge and reality. There tends to be an accepted, dominant paradigm which needs no explanation within their disciplinary community of practice. Studying teaching and learning, however, is much more complex in terms of how it may draw upon many different philosophies and conceptualizations about knowledge, learning, and the nature of “reality.” This complexity, coupled with the multidisciplinary nature of the SoTL landscape, necessitates that researchers be much more explicit about their thinking when presenting their work. In the social sciences, researchers frequently employ the notions of paradigms and methodologies to describe their research.

Research Paradigms

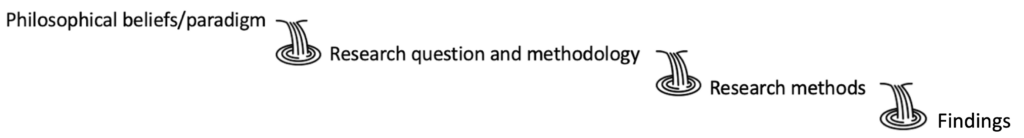

Every research endeavour is grounded in underlying philosophical assumptions, whether these are explicitly articulated or not. These assumptions shape how we formulate and investigate research questions and can be described as a paradigm (Figure 2.1). Philosophers and research methodologists tend to classify research paradigms using three philosophical concepts which are intimately linked:

- the researcher’s worldview, or perspectives on the nature of reality (ontology)

- how the researcher understands things to be known (epistemology)

- the values driving the research (axiology).

Philosophical and methodological debates in research literature, often referred to as the “paradigm wars,” emerged in the latter half of the 20th century. During this period, qualitative researchers championed their approaches against the prevailing Euro-Western paradigms of positivism and post-positivism, while feminist scholars, including those in science and engineering, began to challenge the concept of objectivity in scientific inquiry (Morgan, 2007). These debates persist, and new methodologies are continually emerging and evolving. Thus, the categories outlined here are broad brushstrokes that serve as a guide for positioning oneself within a diverse landscape of practice; however, they are neither perfectly delineated nor exhaustive. Additionally, one should be aware that some of the terms we use below may be defined or applied differently in other discourses.

Positivism

According to Kara’s (2022) historical review, “up to the 1960s research was almost exclusively positivist” (p. 9). Positivist research questions focus on finding predictable and replicable cause-effect relationships that can be used to predict subsequent events and/or generalize across contexts. In other words, they are concerned with building knowledge by testing and refining theory and hypotheses. In this paradigm, a single, observable reality is assumed, and theory provides the explanatory framework that relates the concepts or variables being studied, although the researcher may or may not explicitly state their theory. Knowledge is viewed as cumulative, often leading researchers to identify questions based on gaps in the existing literature. Even smaller, context-specific studies, such as those commonly found in the SoTL literature, can contribute meaningfully within this paradigm, as their findings can be aggregated through meta-analysis. Quantitative experimental research designs, and much research from the natural sciences and some areas of psychology, would fit within this paradigm.

Neo-positivism

The definition of post-positivism or neo-positivism emerged somewhat later. This view recognizes that reality can only ever be partially known or understood because all research has limitations (e.g., biases, accuracy of measurements). As a result, studying cause and effect can only be based on probability. However, researchers within this paradigm still seek to understand a single, external reality through observation and aspire to impartiality and objectivity. Given that phenomena cannot be isolated from context, most quantitative SoTL studies would fit within this category. Empirical qualitative approaches, both deductive and inductive, also fit here. Examples include phenomenography (Chapter 8), template analysis (deductive), content analysis (inductive), and empirical thematic analysis (Yeo et al., 2023). For example, qualitative coding approaches that check for inter-rater reliability fall within this paradigm because of their assumption of a single reality. We put Chapters 7 and 11 in this category because they apply a relatively transparent lens to their analysis, and the former checks for inter-rater reliability.

Critical Realism (an “Intermediate”) Paradigm

There is a substantial gap between positivism and interpretivism. Paradigms that fill this gap do not try to isolate the phenomenon of interest from its context; they explicitly build, refine, or extend theory (rather than test hypotheses) and acknowledge the socially constructed nature of theory. One notable intermediate paradigm that is potentially valuable for SoTL research is critical realism (Miller-Young, 2025). One notable intermediate paradigm that is potentially valuable for SoTL research is realism, a common branch of which is called critical realism (Miller-Young, 2025). This approach focuses on providing contextual and stratified explanations of phenomena; in other words, it asks “why” and “how” questions. The world is viewed as having different layers of reality which are independent of the researcher: the empirical (what can be observed, such as students performing a task); the actual (processes and events, such as student behaviours or decisions); and the real (students’ underlying beliefs or prior conceptions), which result from a combination of “causal mechanisms” (Brown, 2009; Mingers, 2014). In other words, learning is understood as a phenomenon that results from multiple causal mechanisms and can be studied at different levels such as physical, biological, psychological, social, and curricular (Miller-Young, 2025).

In contrast to the natural sciences, social systems are inherently complex and cannot be studied in isolation. Consequently, researchers must depend on abstraction and conceptualization, making explicit use of theoretical frameworks to understand these complexities. Causation, therefore, is not something that can be studied by isolating variables, nor is it expected to be measurable and replicable across multiple contexts. Rather, causation is explained by identifying how, why, and under what conditions causal mechanisms work. Put another way, because of the acknowledgement of complexity, the goals in this paradigm are to explain and anticipate phenomena, rather than to predict. The “critical” aspect of critical realism derives from three features: the recognition that all theories are social constructions; the need for critical self-reflexivity in the research process; and critical realism’s emancipatory potential, based on its aim to identify causal processes, knowledge of which can then inform action (Mingers 2014).

Compared to positivism and interpretivism, this category of paradigms is best defined by its systems ontology. It is also compatible with a broad range of research methodologies, including mixed methods. Paradigms in this category require that researchers practice reflexivity, which involves a keen awareness of their own position relative to the phenomenon under study. Researchers must also continuously reflect on the social, historical, and cultural influences that shape their selection of research questions, theoretical frameworks, and methods. As an example in this book, Chapter 9 uses netnography, a type of ethnographic research conducted online, and positions the learner not as independent from technology but rather as a collaborator with it.

Interpretivism

Researchers using an interpretivist paradigm seek to enrich our understanding of social or cultural events based on the perspectives and experiences of the individuals or groups being studied (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Interpretive researchers view reality as something we, as humans, are a part of, and which therefore cannot be studied independently of us. Rather, they value the researcher’s closeness to the phenomenon being studied and embrace the inevitable subjectivity. Interpretive research therefore involves the generation of qualitative materials for analysis, such as interview transcripts, with the researcher acknowledging that they play an active role in co-constructing the data with participants. These researchers would also describe their positionality and reflexivity as part of the knowledge production process, recognizing that there are varied and multiple meanings that could describe participants’ experiences. Interpretive researchers typically use theory to situate their work within a body of literature but leave it to the reader to determine the transferability of their findings to other contexts. They therefore provide a rich description of the study context. Some research from the social sciences, and much from the humanities, would fit within this paradigm. While not an empirical investigation, we suggest Chapter 5 best fits in this category because it is concerned with meaning-making, plurality, and subjective experiences in education.

Transformative

Transformative methodologies are explicit about causing change through the nature of the research approach itself as well as the knowledge it produces. They aim to expose and reduce power imbalances by collaborating with, rather than conducting research on, marginalized groups. As Creswell and Poth (2018) explain, “the basic tenet of this transformative framework is that knowledge is not neutral and it reflects the power and social relationships within society” (p. 25). A number of research approaches fit within this broad category, including feminist theory, critical race theory, and participatory approaches such as participatory action research and Students-as-Partners (SaP) (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). Researchers using transformative methodologies need to “reflect on their own power and how they use it, as well as the shifting balances and imbalances of power within and beyond the research team” (Kara, 2022, p. 31).

Transformative research is inclusive of a range of methodologies in terms of epistemology and ontology, and is best delineated by its axiology and participatory nature. In this book, Chapter 10 takes a multi-method, empirical approach in terms of methodology and a transformative approach in terms of collaborating with students in all stages of the research process. Chapter 8, on the other hand, demonstrates an interpretive approach to research while also working with students as partners in teaching and learning.

| Category | Nature of Reality (Ontology) | Nature of Knowledge and How It Is Known (Epistemology) | Roles of Values/Drivers (Axiology) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positivism | There is an external reality which exists independently from people | Knowledge builds based on empirical observations | Researcher values objectivity and attempts to control for bias |

| Neo-positivist (Deductive) | Reality is shaped by patterns that emerge within specific contexts | Knowledge is based on established theories and prior evidence | Researcher values objectivity, neutrality, and value-free inquiry |

| Neo-positivist (Inductive) | Reality is shaped by patterns that emerge within specific contexts | Knowledge is constructed and provisional | Researcher values objectivity and strives to minimize researcher influence |

| Intermediate (Critical Realism) | There is a stratified, external reality but it is inseparable from context | Knowledge is socially and historically produced | Researcher values objectivity but also acknowledges their positionality |

| Interpretivism | Reality does not exist independent of people; people interpret facts and phenomena | Knowledge comes from co-constructing meaning from experience | Researcher values subjectivity |

| Transformative | People experience multifaceted realities influenced by their social location | Knowledge comes from co-constructing meaning | Researcher seeks social justice through emancipatory and collaborative processes |

Note. Adapted from Ling (2019), Miller-Young (2025), and Yeo et al. (2023)

Research Methodologies

As Miller-Young and Yeo (2015) explain, research methodologies are more than simply a “description of how the participants were selected, and the data collected and analyzed. Methodology explains why it was done this way” (p. 42), aligning the philosophical assumptions of the research with the methods employed and demonstrating how theory frames and informs the study. In this next section, we briefly describe a few broad categories of methodologies and refer the reader to Yeo et al. (2023) for more detailed descriptions of both methodologies and methods.

Quantitative Research Methodologies (Designs)

Quantitative research, as its name suggests, relies on numerical data and measurements. The aim is to simplify complexity and identify patterns within large datasets, employing a deductive approach where theory and literature precede data collection. Theory guides the formulation of hypotheses and informs decisions on which variables to measure and control. Because there is no possibility for further interpretation once the data is collected, quantitative research requires a substantial amount of work upfront to ensure that measurements are valid, reliable, and repeatable. It must also ensure that a study will have statistical power; in other words, that the measurements are meaningful and that the statistical findings are likely not due to random chance.

Common quantitative educational research designs and the types of questions they ask include (quasi-)experimental designs (What is the effect/impact of x on y?), correlational designs (What is the relationship between x and y?), and survey designs (How are certain variables/characteristics distributed within a population?). Depending on the phenomena being studied and the use of theory and/or participatory methods, quantitative studies may fall within the positivist, neo-positivist, critical realist, or transformative paradigms.

Qualitative Methodologies

Although educational technology research has often been characterized by a dominance of quantitative methods, qualitative research holds significant potential for addressing the complex challenges that educational technologies seek to overcome (Henrich, 2024). The purpose and value of qualitative research lie in its capacity to explore complex phenomena in depth. Qualitative methodologies are highly diverse, drawing on various epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies (Tracy, 2010). They can be both inductive and deductive, accommodate different degrees of researcher objectivity or subjectivity, and use materials such as interview and focus group transcripts, narratives, documents, and photographs as data sources. Theory may serve both as an orientation to the research and a lens for data analysis.

When using what are often called “qualitative empirical” (Miller-Young & Yeo, 2015; Yeo et al., 2023) or “small q” approaches (Braun & Clarke, 2013), researchers use a relatively transparent lens, taking the data at face value and assessing the trustworthiness of their findings through processes such as triangulating multiple sources of data, determining inter-coder reliability, and member checking. Such studies would fit within a neo-positivist or critical realist paradigm. Phenomenography and case study are the most common examples (case studies can involve triangulating both quantitative and qualitative data, but still take an overall qualitative approach to the research compared to mixed methods; see below).

Interpretive qualitative research (or “big Q” [Braun & Clarke, 2013]) is more commonly used when studying culture and experiences. The researcher acknowledges the important role of both the context of the research and the co-constructed nature of the resulting knowledge. Trustworthiness and “generalizability” are addressed differently in this paradigm because of the co-constructed nature of knowledge. Criteria for quality research include thick description, triangulation, and resonance (Tracy, 2010). Examples of interpretive methodologies include ethnography (for questions about culture), narrative inquiry (for making meaning from people’s stories), and phenomenology (for questions about the essence of experience). Grounded theory is another qualitative, interpretive methodology that is explicitly inductive and used for building new theory.

Mixed Methodologies

True Mixed Methods (big M) research presents valuable opportunities for SoTL researchers by integrating the broad insights of quantitative research with the deep understanding of qualitative research. However, it demands a broader range of expertise, necessitating proficiency in both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. To be clear, the methodological category of “Mixed Methods,” despite the unfortunate name, involves more than simply collecting quantitative and qualitative data (better described as multi-method or case study, as noted above). It is defined by having a quantitative component (that meets the standards for quantitative research, such as statistical power) and a qualitative component (that meets the standards for qualitative research) as well as by integrating the findings from both components in order to derive insights that could not be found using qualitative or quantitative methods alone.

Given its integration of diverse qualitative and quantitative traditions, some argue that Mixed Methods research constitutes its own paradigm, often referred to as pragmatism (Morgan, 2007). Nevertheless, the quantitative and qualitative elements within a Mixed Methods study usually maintain their distinct philosophical approaches and assumptions, as outlined previously. Components of a study can be conducted sequentially or concurrently. Mixed Methods studies are also highly compatible with critical realism (Yeo et al., 2023).

Aligning your underlying philosophical assumptions with your research questions, paradigms, and methodologies is essential for developing and conducting an effective SoTL research study. By making these choices explicit, you strengthen the design and coherence of your work, and improve your ability to communicate its significance and impact to interdisciplinary audiences.

The next chapter will expand on how theory can also play an important role in SoTL.

Reflective Questions

- What are the epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies of your discipline?

- What research paradigms are you most comfortable with in terms of informing your teaching and research practice?

- What research paradigms are you most comfortable with in terms of conducting your own SoTL research?

- How do you position yourself in your research?

- How do you communicate your philosophical beliefs and values to others?

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

Brown, G. (2009). The ontological turn in education: The place of the learning environment. Journal of Critical Realism, 8(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1558/jocr.v8i1.5

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Divan, A., Ludwig, L. O., Matthews, K. E., Motley, P. M., & Tomljenovic-Berube, A. M. (2017). Survey of research approaches utilised in the scholarship of teaching and learning publications. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 5(2), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.5.2.3

Haigh, N., & Withell, A. J. (2020). The place of research paradigms in SoTL practice: An inquiry. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 8(2), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.8.2.3

Kara, H. (2022). Qualitative research for quantitative researchers. Sage.

Ling, L. (2019). The power of the paradigm in scholarship in higher education. In Emerging methods and paradigms in scholarship and education research. IGI Global.

Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, K., Marquis, E., Shammas, R., & Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

Miller-Young, J., & Yeo, M. (2015). Conceptualizing and communicating SoTL: A framework for the field. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 3(2), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.3.2.37

Miller-Young, J. (2025). Asking “how” and “why” and “under what conditions” questions: Using critical realism to study learning and teaching. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 13. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.13.40

Mingers, J. (2014). Systems thinking, critical realism and philosophy: A confluence of ideas. Routledge.

Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292462

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. Sage.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

Yeo, M., Miller-Young, J., & Manarin, K. (2023). SoTL research methodologies: A guide to conceptualizing and conducting the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003447054

Media Attributions

Figure 2.1. Waterfall image by icons8 on Icons.com is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.