11 Challenging Assumptions About HyFlex Teaching with Students as Partners

Zoya Adeel; Stefan M. Mladjenovic; Kate Brown; Sara Smith; and Katie Moisse

Introduction

Undergraduate students in our context are clamouring for flexibility in their education. Some need flexibility because of disabilities, while others are juggling caregiving or employment responsibilities. Some worry about the ongoing health risks of attending lectures during a pandemic or some need flexibility because they are sick. Some students are unable to afford housing near campus, forced to weigh the risks of a snowy drive or late-night bus ride in deciding whether they can safely come to class.

We learned all this from listening to undergraduate students in the Honours Life Sciences program at McMaster University, first informally and then formally through surveys and focus groups. McMaster University is located in Ontario, Canada, and is home to over 30,000 undergraduate students across five faculties each year. The Honours Life Sciences program is the largest undergraduate program at McMaster, with over 1,026 students enrolled during the 2022–2023 academic year.

The students to whom we have listened to make a compelling case for hybrid-flexible (HyFlex) learning environments, wherein they have the option to learn in a physical classroom or virtually depending on their circumstances and preferences. However, some instructors worry about attendance crashing and pulling student grades down with it. Other instructors feel there are important benefits to being in the classroom, including opportunities to connect with professors and peers, while other instructors fear the burden of creating a HyFlex learning environment and supporting all the students within it.

So, we must ask important questions:

- Can we honour student preferences without harming their learning experience or the teaching

experience of instructors? - Does providing the flexibility that students want and, in many cases, need diminish the learning experience for some, or could it enhance the learning experience for all?

Asking these questions requires challenging our assumptions as both teachers and learners.

Our student-partnership approach to this study was intended to address power imbalances between the instructor and student by collaborating with students in the research process, rather than conducting research on students (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). This aligns with our underpinning desire to prioritize the individual perspectives of students and enable agency in how students engage in their learning (Miller-Young & Yeo, 2015; Crompton, 2013).

By using both quantitative and qualitative methods and a transparent lens, our study fits within the category of a neopositivist paradigm (see Chapter 2). We reflect our research philosophies in our student-partnered-informed, multi-method study that combines grades, measures of engagement, surveys and focus groups, through which we listened carefully to diverse perspectives and thought critically about the aims and outcomes of our HyFlex teaching practice at McMaster University. In sharing our approach and findings, we hope to provide a compelling case for student-partnered research that examines, both quantitatively and qualitatively, the impact of honouring student needs and preferences by incorporating flexibility into higher education through the use of technology.

The authors of this chapter contributed in various roles to the design, delivery, and interpretation of this research:

- Zoya Adeel and Stefan Mladjenovic, as students in a participating HyFlex course, informed the study design and interpreted the findings as student partners.

- Kate Brown provided insight on the design and research findings through her lens as an expert in diversity, equity, and inclusion in post-secondary education.

- Dr. Sara Smith conducted the data analyses.

- Dr. Katie Moisse, the instructor of all participating HyFlex courses and the study’s primary investigator, led the overall design, delivery, and interpretation of this research.

HyFlex Learning Environments

The term “HyFlex” describes “class sessions that allow students to choose whether to attend classes face-to-face or online, synchronously or asynchronously” (Beatty, 2019). According to Beatty, HyFlex courses (Chapter 1.3):

- give students agency over how they will attend a session;

- provide equivalent learning activities in all modes;

- use the same learning objects for all students;

- ensure students are equipped with the technologies and skills to participate in all modes; and

- employ authentic assessments that are relevant and have real-world applications.

Prior research evaluating HyFlex has generally found that the option to attend class either in person or online does not negatively affect student attendance, engagement, or final course grade (Groen et al., 2016; Lakhal et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2013; Adeel et al, 2023). Miller et al. (2013) found that when students are provided the option to attend class asynchronously with recorded lectures, 61% of undergraduate students self-reported that they did not miss any class in an undergraduate HyFlex statistics class (n = 157). They also found no difference between homework grades, midterm scores, and final course grades between students who attended the course synchronously in person or online. Similar research conducted by Lakhal et al. (2014) found no significant differences in student satisfaction, multiple-choice texts, and written exam scores between students who chose different attendance modes. Another study found that HyFlex learning environments were associated with an increase in course enrolment and student satisfaction (Sowell et al., 2019).

We sought to validate these findings in our context with a Students as Partners approach to elevate the perspectives of students and enable agency in how students engage in their learning. We also aimed to counter key assumptions of our instructors and administrators related to online and HyFlex learning in undergraduate classrooms.

Echo360 as a HyFlex Teaching and Learning Platform

Echo360 is an educational technology that can be leveraged to align with Beatty’s five fundamental principles of HyFlex courses. It complies with provincial accessibility standards and is institutionally supported at McMaster University and, therefore, free for students and instructors to use. More than 90 McMaster classrooms are equipped with equipment that enables instructors to schedule synchronous live streams of their lectures and/or record lectures for later, asynchronous viewing using Echo360. Even in classrooms without a built-in Echo360 system, instructors can livestream and record from their laptops. All recordings generate a searchable transcript that can be applied to closed captions.

Instructors can use Echo360 features to engage students in active learning. For instance, they can embed interactive slides that use polls or short-answer questions to gauge students’ understanding of concepts or solicit their perspectives for discussions. A Question & Answer feature allows instructors and students to share queries, comments, and files, with or without anonymity. Students and instructors can respond to and endorse comments, creating a vibrant online discussion in addition to any in-person discussion. Students can also anonymously raise a “confusion flag” when concepts are unclear, prompting the instructor to clarify. Importantly, students can engage with these features anonymously, which is more comfortable for some students than speaking out in class

(Hoekstra, 2008).

Echo360 also provides analytics that can help instructors monitor student engagement, if they wish. Instructors can measure attendance and engagement with interactive slides. They can link these metrics to their learning management system so that attendance and/or participation contribute to student grades. In our experience, attaching a small grade value to student engagement encourages attendance and participation. However, we recognize there are different views among instructors on the pedagogical merits of “participation marks” (Mello, 2010; Paff, 2015).

Designing and Conducting Research With Students as Partners

Our research originated from conversations with students in various venues—in the classroom while collecting midterm feedback, during office hours while meeting with students, and in round-table discussions with student groups. Students shared how much they wanted and needed flexibility and what it meant for them to have it. However, they understood that sharing their experiences in these forums alone would not lead to broad adoption of HyFlex teaching practices. They needed data.

At the start of the 2019–2020 academic year, we formed a partnership to explore student experience with HyFlex teaching and learning. We decided to use Echo360 to create a HyFlex learning environment not only because of its active learning and accessibility features but also because of the data it could provide. We did not want to force students to engage either in person or virtually—flexibility was key. So, we designed an empirical study wherein we could compare outcomes between learners who chose to participate predominantly in person or online. We also used surveys and focus groups to explore student experiences of the HyFlex learning environment and better understand their desire for flexibility. Our multiple methods allowed us to better understand students’ experiences of the HyFlex environment.

Over the past five years, we have used this approach to test five assumptions about HyFlex teaching and learning that we had informally gathered from instructors and students:

- When given the option to participate virtually, in-class attendance will be low.

- Students who participate primarily online will have reduced engagement and lower grades

compared to those who participate primarily face -to -face. - Students perceive that a HyFlex format can support success, particularly students with flexible

learning needs. - Our pre-COVID findings will hold up in a post-COVID context.

- Students will report weak connections between peers and their instructors in a HyFlex learning

environment.

We tested our first three assumptions during the 2019–2020 academic year and published these findings in The Canadian Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (Adeel et al., 2023). We built on these findings to design a follow-up study in the 2022–2023 academic year that tests Assumptions 4 and 5.

Students were partners at every step of the research process. They decided which outcomes we should measure, wrote the ethics protocols, co-designed the survey questions, ran focus groups, analyzed data, shared findings at meetings and conferences, and submitted their work to a pedagogical research journal. This partnership has been critical in asking meaningful research questions and getting honest input from students. It has also forced all of us—students and instructors alike—to challenge the assumptions we make about the best ways to teach and learn.

Below, we describe our ongoing study, which has so far spanned four years with seven student researchers and 875 student participants. We hope that by describing our process, we can inspire others to stay reflexive in their teaching practice as student needs and institutional environments evolve.

Study Design

Context

Our study began in the 2019–2020 academic year when we ran two third-year life sciences courses in a HyFlex format using Echo360. Students were required to participate synchronously, either in person or online, and asked to share their mode of participation at the start of each class in a polling question. They were also asked to engage with interactive slides during class (synchronously) and in preparation for class (asynchronously) based on required readings/viewings. Synchronous attendance during class time and polling participation before and during class contributed to an “engagement score” worth 4–5% of students’ final grade, depending on the course. The methods are detailed in Adeel et al. (2023).

Both courses were lecture-based, with 125–150 students, but they differed in their disciplinary focus and format:

- LIFESCI 3P03: Science Communication in the Life Sciences, is a skills-based course that is highly

interactive. - LIFESCI 3Q03: Global Human Health and Disease, is a content-based course that is moderately

interactive.

The interactivity forms the rationale for requesting synchronous attendance: We believe students benefit from listening to and sharing perspectives in real-time. All students enrolled in LIFESCI 3P03 and LIFESCI 3Q03 were informed at the start of the term that their Echo360 engagement and grades were being collected for research purposes.

Our study continued during the 2022–2023 academic year, using the same methods as in the 2019–2020 cohort but in a post-COVID context. We focused on LIFESCI 3P03 and a large-enrollment second-year life sciences course, LIFESCI 2AA3: Introduction to Topics in the Life Sciences. As before, students were required to participate synchronously, either in person or online, and were asked to share their mode of participation and engage with interactive slides during class.

LIFESCI 3P03 remained unchanged from the 2019–2020 to the 2022–2023 academic year, while LIFESCI 2AA3, a skills-based and interactive, enrolled nearly 300 students. All students enrolled in both LIFESCI 3P03 and LIFESCI 2AA3 were informed at the beginning of the term that their Echo360 engagement and grades would be collected for research purposes.

Methods

To test Assumption 1—when given the option to participate virtually, in-class attendance will be low—we compared student attendance between in-person-dominant and online-dominant learners in both cohorts. In-person- dominant learners participated in more than half of the course lectures in person; while online- dominant learners participated in more than half of the lectures virtually.

Next, to test Assumption 2—students who participate primarily online will have reduced engagement and lower grades compared to those who participate primarily face to face—we compared student engagement and final grades between in-person-dominant learners and online-dominant learners. Final grades were adjusted to remove the contribution of the engagement score. Students that attended class in person or online more than half the time were categorized as in-person dominant or online-dominant learners, respectively, and those that attended class in person and online evenly were categorized as “equal.” Statistical analyses associated with testing Assumption 2 were conducted in R (v.4.4.2, R Core Team 2024).

To test Assumption 3—students perceive that a HyFlex format can support success, particularly students with flexible learning needs—we also conducted a survey and focus groups to understand why students want or need flexibility and to explore their perceptions of a HyFlex teaching and learning platform. In November 2019, we sent a questionnaire to all life sciences students. We had 238 respondents, 11 of whom also signed up to participate in a one-hour focus group facilitated by two student partners. The questionnaire included 24 items and included both multiple-choice and short-answer questions. The focus group included a guided discussion that probed deeper into students’ experiences in the Hyflex classroom.

To test Assumption 4—our pre-COVID findings will hold up in a post-COVID context—we repeated our study in the 2022—2023 academic year in LIFESCI 3P03: Science Communication in the Life Sciences, and LIFESCI 2AA3: Introduction to Topics in the Life Sciences. Both courses are skills based and highly interactive, with 300 students each. We sent an updated version of our questionnaire to students enrolled in either course after the end of the term to gather their perspectives on learning in a Hyflex classroom. The updated questionnaire expanded on the previous survey, incorporating additional questions that explored the student experience of attending class in person or online in a Hyflex setting. This allowed us to probe further on sentiments related to online learning that emerged during the pandemic.

To test Assumption 5—students will report weak connections between peers and their instructors in a HyFlex learning environment—we asked students in the 2022–2023 academic year to report how their peer’s virtual participation in class impacted their sense of connectedness in an in-person setting in the questionnaire.

Findings

Assumption 1: When Given the Option to Participate Virtually, In-Class Attendance Will Be Low

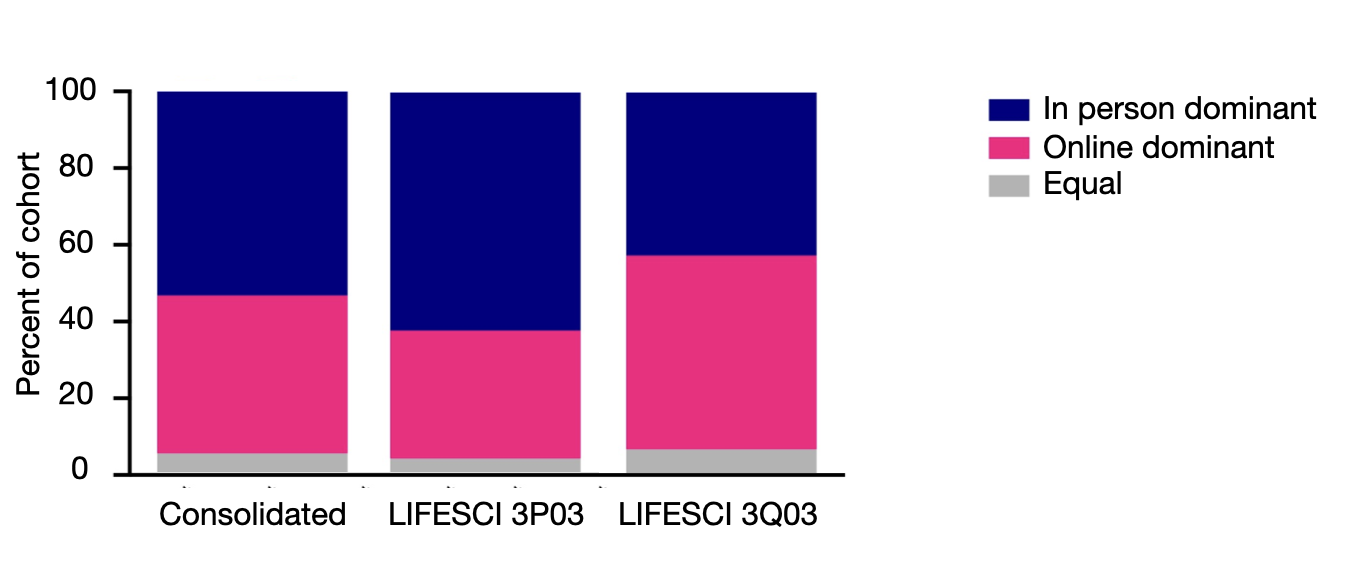

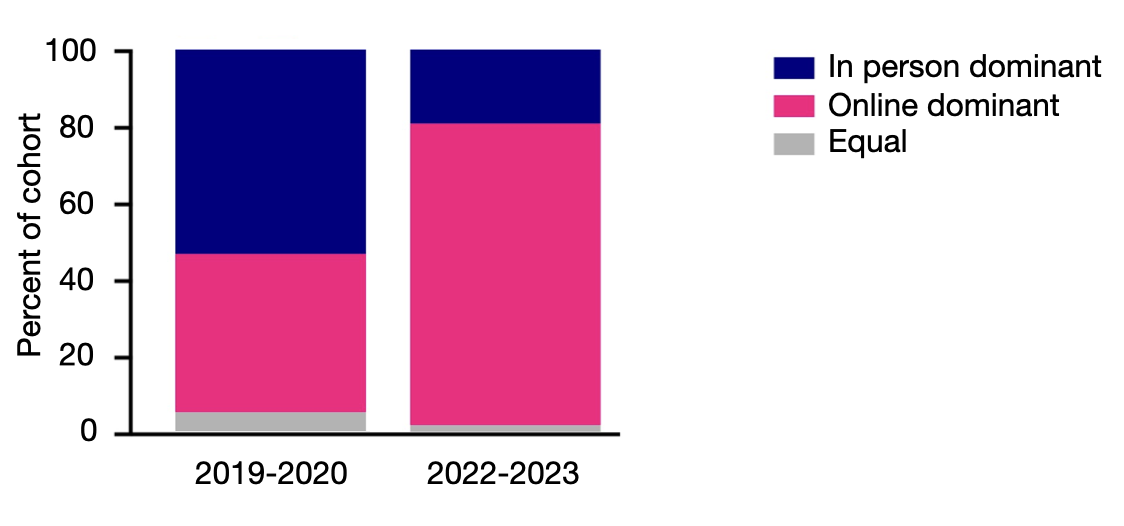

When given the choice to participate in the classroom or virtually, in the 2019–2020 academic year, a slight majority of students came to class over half of the time (Figure 11.1). On average, in-person-dominant learners attended 79% of their classes in person in LIFESCI 3P03 and 71% in LIFESCI 3Q03. Online-dominant learners attended 71% of their classes online on average in LIFESCI 3P03 and 79% in LIFESCI 3Q03.

LIFESCI 3Q03 had more online-dominant learners than LIFESCI 3P03 (51% vs 35%), but it is worth noting that LIFESCI 3Q03 ran in the winter of 2020, when COVID-19 forced universities to close in March and the students were required to attend class virtually for the last three weeks of the semester. Based on previous experience in large-enrolment courses, we feel that having 53% in- person-dominant learners refutes our assumption that in-class attendance will plummet. It is worth noting that attendance typically fluctuates across the semester and did in our case:

At the start of LIFESCI 3P03, 70% of students participated in person, 22% participated online, and 9% did not respond to the polling question. Towards the end of term, 41% of students participated in person, 53% participated online, and 6% did not respond to the polling question. In both classes, we had a greater than 90% attendance rate, which we suggest would have been lower if the online option was not available.

Assumption 2: Students Who Participate Primarily Online Will Have Reduced Engagement and Lower Grades Compared to Those Who Participate Primarily Face-To-Face

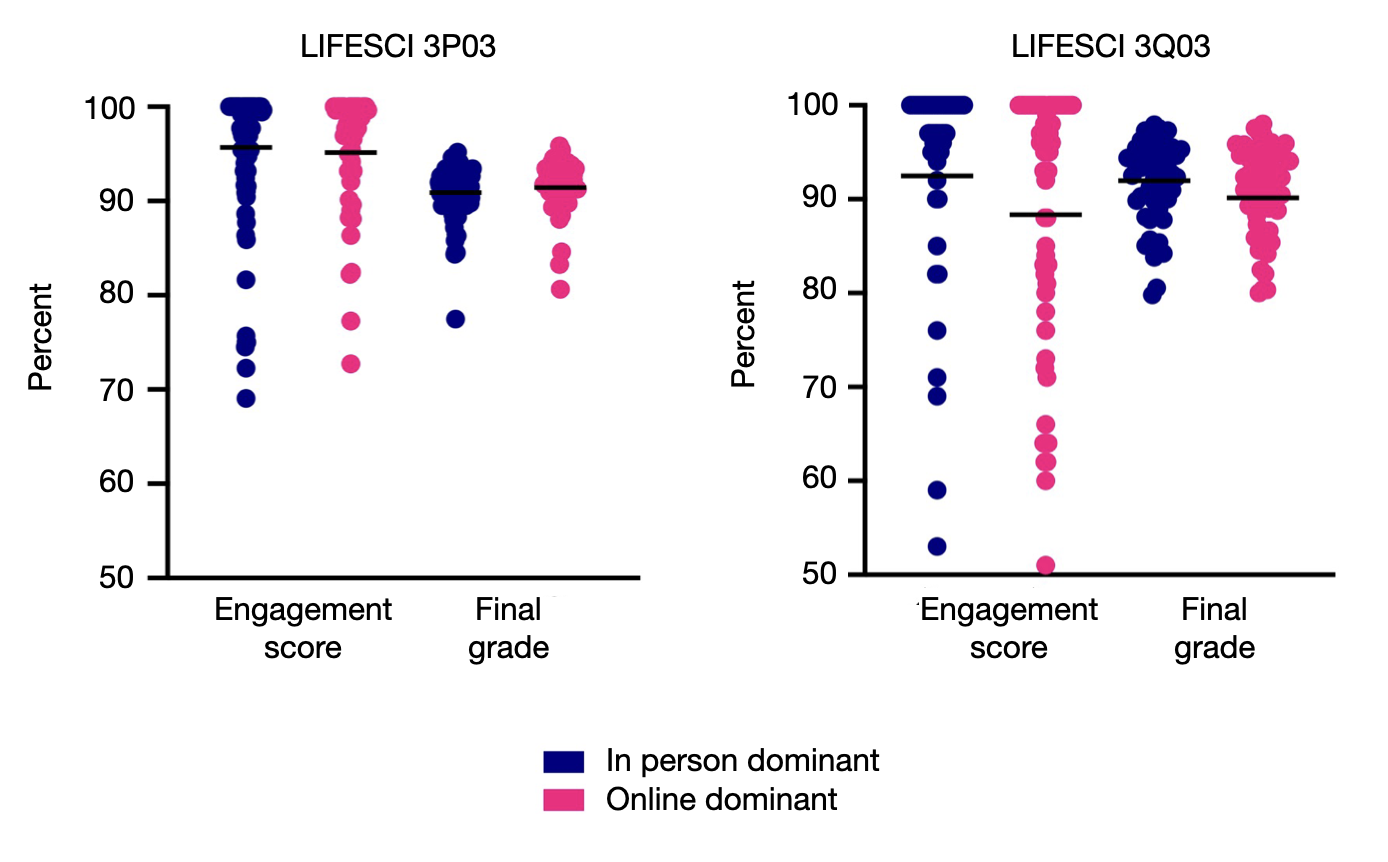

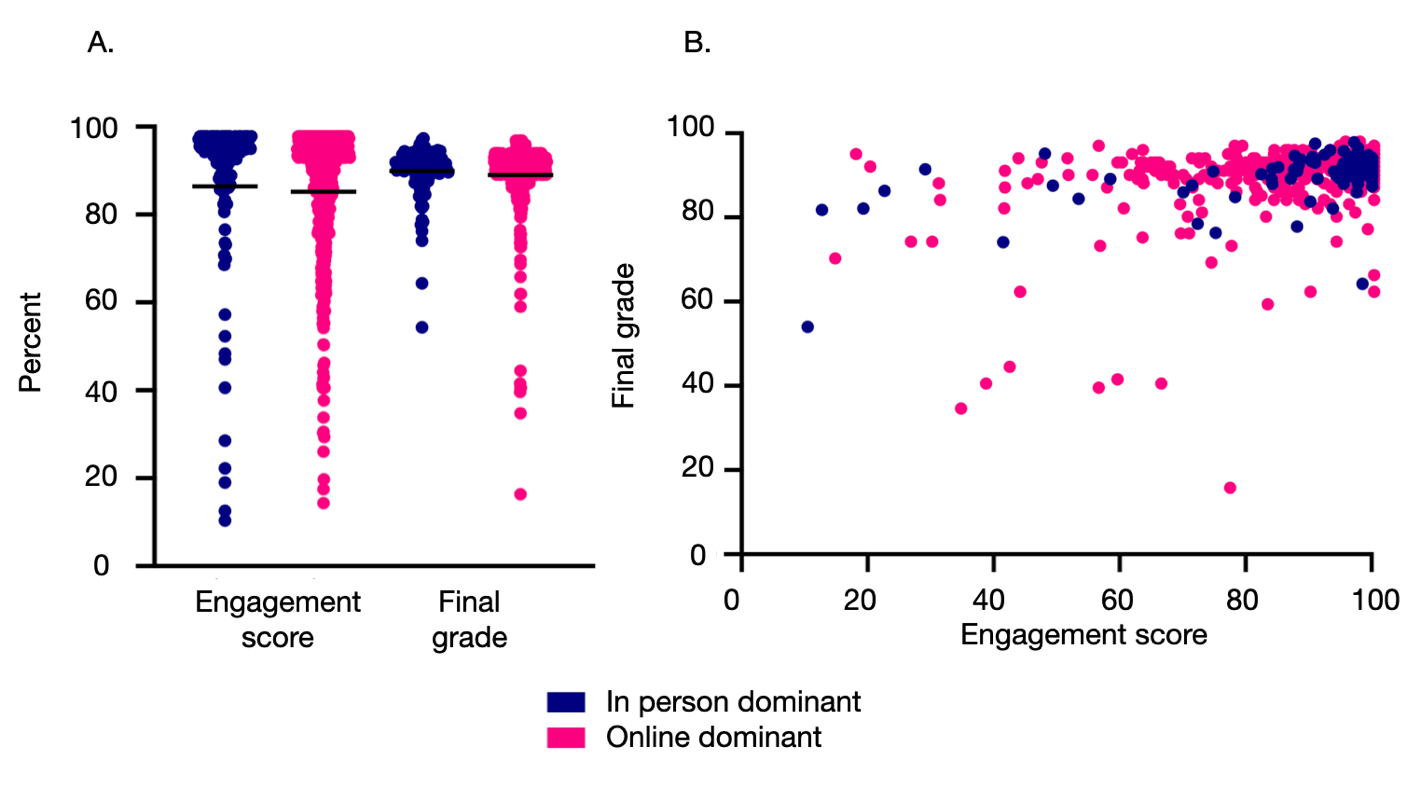

We compared the engagement scores and final grades between in-person-dominant and online-dominant learners across both cohorts using Kruskal-Wallis tests to assess differences between these learners. We assessed both the engagement in course content and the final grade between modes of delivery. We saw no difference in engagement score or final grade (adjusted to remove the 4–5% contribution of the engagement score) between the two types of learners in both LIFESCI 3P03, a skills-based course, and LIFESCI 3Q03, a content-based course (Figure 11.2). This suggests students can be successful in our courses by making their own decision about the participation mode that works for them, even in highly interactive learning environments.

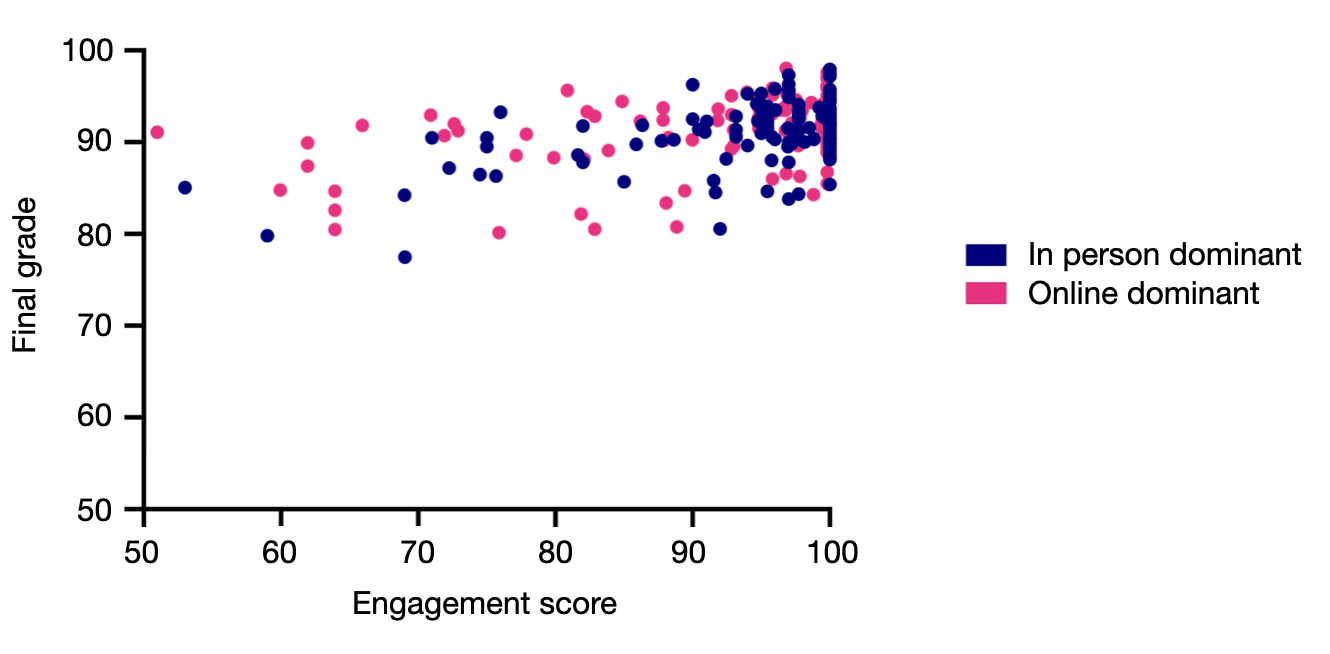

Using the Pearson correlation test, we saw a correlation between engagement score and final grade in both groups (Figure 11.3).

Assumption 3: Students Perceive That a Hyflex Format Can Support Success, Particularly Students With Flexible Learning Needs

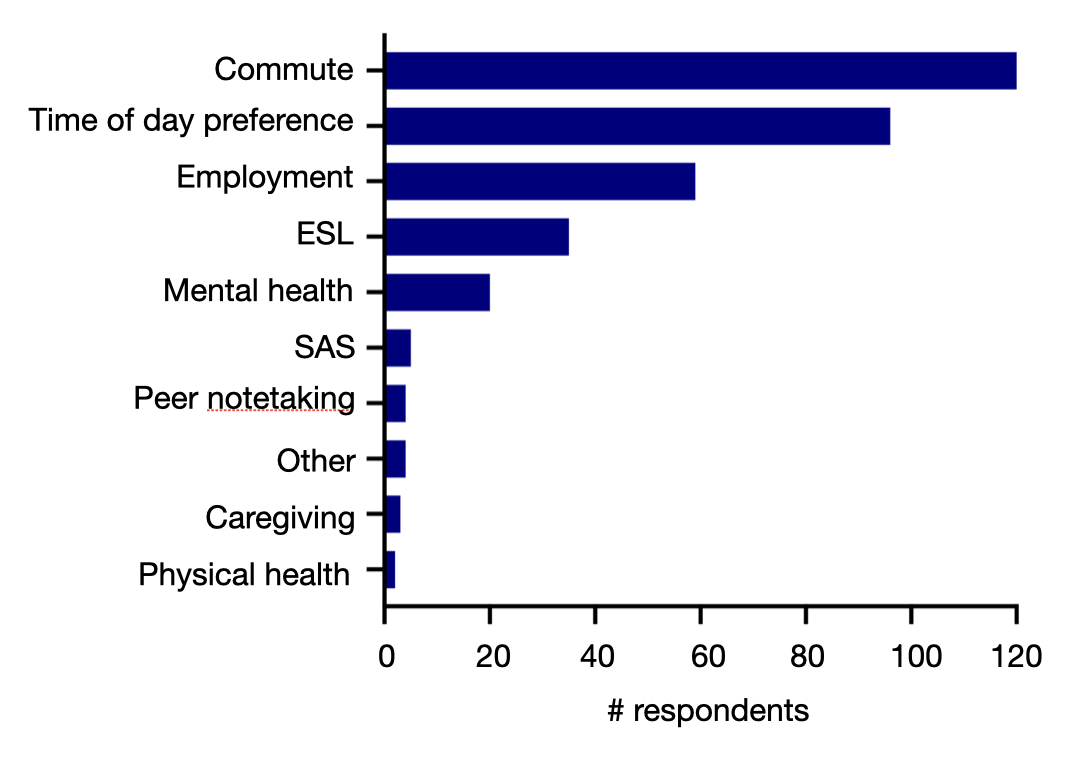

Of the 1,198 honours life sciences students that were invited to participate, we received 238 responses to our survey probing students’ perceptions (response rate of 19.9%). Of the 238 survey respondents in the 2019–2020 academic year, 209 (88%) identified at least one flexible learning need, such as commuting, working one or more jobs, or speaking a first language other than English (Adeel et al., 2023, Figure 11.4).

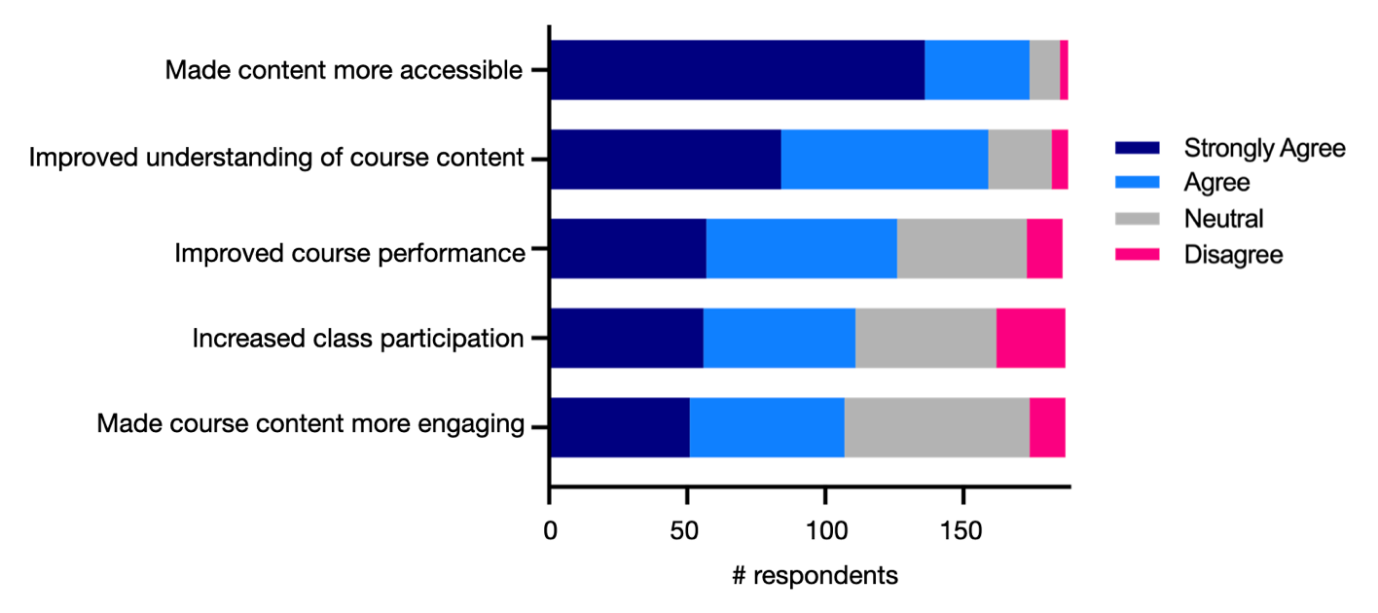

We also asked students to reflect on their experience with Echo360 (Figure 11.5). Among students who had used the platform (n = 189), 92% said using Echo360 made course content more accessible and 84% said it aided their understanding of course content. Importantly, of the 173 students who had used Echo360 and identified at least one flexible learning need, 172 (99%) said Echo360 benefitted them in some way. This suggests students perceive a benefit to HyFlex learning environments and feel it supports their success.

In our focus groups, students shared that they want to come to the classroom but want the option to participate virtually when necessary. “I would still rather go to class, but if you can’t come, it still leaves you with other options,” one student shared. “It’s that second option if you can’t make it to lecture,” another said. For some students, though, the virtual option made learning more comfortable. “I think it is easier to be online. Sometimes it can be intimidating to go in,” one student shared. “It’s also convenient. My schedule doesn’t always work with office hours, so I can just ask questions on the discussion [board].”

Assumption 4: Our Pre-Covid Findings Will Hold Up in a Post-Covid Context

Our data from the 2019–2020 academic year provided compelling evidence for HyFlex learning environments in large-enrolment courses. However, we did not want to assume that our pre-COVID findings would hold up in a post-COVID context, wherein some instructors have noticed significant drops in attendance and student grades.

When given the choice to participate in the classroom or virtually in the fall of 2022, most students chose the virtual option most of the time (Figure 11.6). In LIFESCI 2AA3, 216 out of 300 students (72%) attended more than half the classes virtually, and 16 (5%) attended every class virtually. In LIFESCI 3P03, 237 out of 300 students (79%) attended more than half of the classes virtually and 57 (19%) attended every class virtually.

On average, in-person-dominant learners attended 93% of their classes in person in LIFESCI 3P03 and 92% in LIFESCI 2AA3. Online-dominant learners attended 91% of their classes online on average in LIFESCI 3P03 and 93% in LIFESCI 2AA3.

Despite a shift toward virtual attendance, we still saw no difference in final grades between in-person-dominant and online-dominant learners using a Kruskal-Wallis test (p = 0.222, Figure 11.7). This aligns with our previous findings and gives us more confidence that participating primarily online does not negatively impact student achievement. We did, however, see a small but statistically significant dip in engagement scores among online-dominant learners compared with in-person-dominant learners (p = 0.00272). We once again saw a correlation using the Pearson test between engagement and final grade (p < 2.2e – 16), suggesting that perhaps interactivity and engagement are more important to student success than whether they are in person or online. However, testing this interpretation would require further research.

For the implementation of the fall 2022 survey, roughly 800 students were invited to participate, and 109 responses were received. About 70% of respondents said they attended at least one class virtually because they were unwell, and 32% said they attended at least one class virtually because they were worried about getting sick. Conversely, 5% of students said they attended at least one class in person because they did not have the resources—such as technology, Wi-Fi, or a quiet space—to attend class virtually. These findings support the need for HyFlex learning environments wherein students can choose how to learn based on their circumstances.

We also used the survey to explore student perceptions of our HyFlex courses. All 109 respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I benefited from the flexibility of being able to participate in this course either in person or online.” About 93% either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “The option to attend class synchronously online made me more likely to attend lectures in this course.” And about 69% either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “My attendance in this course was higher compared to courses that are only in person.” These findings suggest that students want flexibility, are more likely to participate in a HyFlex learning environment, and feel flexibility enhances their learning experience.

In open-field responses, students expressed appreciation for flexibility and choice. In fact, some shared that flexibility heavily influences their course selections. “The option to participate in class online/have lectures recorded is a huge component when I’m deciding what courses to take. I get sick often and it is hard for me to come to campus for every class, so having an online option is ideal,” one student shared. “The online option made me decide to take the course. I like to have the flexibility and the opportunity to listen [to] the lectures again and again to better understand and practice the course content,” another reported. Another said, “Thank you for allowing students to make their own decisions for their learning.”

Assumption 5: Students Will Report Weak Connections Between Peers and Their Instructors in a Hyflex Learning Environment

We asked students in our HyFlex courses from the 2022–2023 academic year how connected they felt with their peers and their instructor. About 67% of respondents said they felt very or somewhat connected to their peers, and 82% of students said they felt very or somewhat connected to their instructor. Interestingly, 44% of students said they felt more connected to their peers in their HyFlex course than in courses that are in person only, compared with 35% who said they felt less connected to their peers. Additionally, about 72% of students said they felt more connected to their instructor, compared with 16% who said they felt less connected. The findings from our focus groups suggest HyFlex learning environments can create additional avenues for connection that may be more comfortable for some students. Indeed, our survey found that roughly 92% of students either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I was more likely to participate and ask questions because I had the option to attend class based on my preferences.”

Conclusion

Our findings validate previous findings that student attendance and academic outcomes are not negatively affected by having the option to attend class virtually. We demonstrate this with empirical evidence and from the perspectives of students. We did find evidence of an increased preference for online learning and a small decrease in engagement among online-dominant learners in our most recent cohort, but we continue to see a correlation between engagement and final grades among both in-person-dominant and online-dominant learners.

We sought to test five assumptions about HyFlex teaching and learning. Our findings do not outright refute the assumption that in-class attendance will plummet if students have the option to participate virtually. During the fall 2022 offering of LIFESCI 3P03, in-person attendance varied from 46% at the start of the term to 12% at the end of the term. That said, we still had 90% attendance at the end of the term, which is high relative to other large-enrolment courses with no virtual option. The observed shift toward greater virtual participation in the post-COVID context suggests the benefits of coming to the physical classroom need to outweigh the perceived risks and costs (i.e., the risk of illness, the cost of commuting, the cost of time spent getting to and from campus instead of working or studying, etc.). This meshes with student responses to our survey about avoiding campus because of illness or the perceived risk of illness.

Students report that the HyFlex format can also support student attendance and success, particularly among students with flexible learning needs, in both pre-and post-COVID contexts. This change since the 2019–2020 academic year could reflect a shift in preferences now that students have more experience with virtual learning. It could also reflect an increase in flexible learning needs, including worries about getting sick. Of the 3,458 students with accommodations through McMaster’s Student Accessibility Services in the 2022–2023 academic year, 1,135 had accommodations for missed classes, and/or work, 1,165 had accommodations to record lectures, and four requested remote learning access (Shih, 2023, personal correspondence).

Finally, our findings challenge the assumption that a HyFlex learning environment will weaken connections among students and with their instructors, as more students reported stronger connections with their peers and instructors in HyFlex courses than those who reported weakened ones. Because students chose their preferred mode of participation from week to week, it is possible that students who participated primarily online prefer online interactions, including the anonymity of asking questions and participating in polls through Echo360. It is important to acknowledge that some students (32% of survey respondents) felt that the option to participate virtually compromised the in-person learning experience. About half of these students participated primarily in person, and the other half primarily online. This high percentage, combined with the experience of some students with reduced connections with peers and their instructor, highlights a critical consideration when creating and managing HyFlex learning environments: We must balance students’ desire for flexibility with the consequences of providing it.

We are taking steps to modify our courses to address some of the concerns raised by our respondents. Specifically, we recognize that many students are now participating exclusively online. For these students, we are creating an online section of select courses in which lectures meet the highest standards of accessibility and can be experienced asynchronously (on a schedule), with virtual office hours and group projects. We will run, in parallel, a Hyflex offering of these courses for students who wish to participate primarily in person. This Hyflex offering could be run in a smaller classroom outfitted for Hyflex course delivery, thus addressing student concerns about the in-person experience.

Our student-partnered approach was essential in identifying common assumptions about HyFlex teaching and learning and designing research questions and methodologies that could meaningfully and ethically challenge those assumptions. Students bring valuable lived experiences to pedagogical research (Matthews, 2018). They also understand the need to set their personal preferences aside and understand perspectives different from their own (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). The student partners on this project are exceptional listeners and critical thinkers, and our research is better for it.

Future Direction

We must continue to explore and identify the limits of HyFlex teaching and learning environments. Class size, level, and subject matter all influence course design, and it is very likely that certain types of courses are more amenable to HyFlex learning environments than others. We must also capture honest input from instructors to understand the perceived downsides of HyFlex teaching, including concerns about increased workload. A 2021 study found that faculty members felt less prepared to manage the intricacies of HyFlex teaching than those of in-person teaching. Although instructors saw the pedagogical merits of HyFlex instruction, they needed significant support and resources in designing and implementing a HyFlex course (Romero-Hall & Ripine, 2021).

In the next phase of our study, we wish to explore the impact of HyFlex learning environments on the number and nature of accommodation requests. The number of students with disability-related accommodations grew from 3,124 in the 2019–2020 academic year to 4,280 in 2021–2022 and 3,458 in 2022–2023. We now have evidence that, for some students, having a virtual avenue to learn means attending class when they otherwise would not. Students who miss class with any frequency may feel less prepared than their peers, and this lack of preparation may be a significant driver of accommodation requests. Students with disability-related accommodations have shared anecdotally that they benefit greatly from the option to participate virtually when needed. We plan to compare the number and nature of accommodation requests in HyFlex courses to the number and nature of requests in courses of similar sizes with similar assessment structures delivered in a traditional classroom environment. We endeavour to do this in partnership with students who have flexible learning needs, including students with disabilities.

We must continue to challenge our assumptions as teachers and learners as partners in discovering ways to make education more flexible and accessible. Our student-partnered approach strengthened the questions we asked and our approaches to answering them. We commit to further enhancing the quality and relevance of our work through meaningful partnerships with students. We hope our work will inspire instructors and students to partner in challenging assumptions at their institutions about the best ways to teach and learn.

Reflective Questions

We pose the following series of questions for the reader to reflect on:

- What are your assumptions about flexibility in teaching and learning? How can you challenge those assumptions in your classroom?

- How can current teaching practices be reframed to promote student agency over their learning?

- What are ways to leverage existing educational technology platforms to elevate the student learning experience, both in -person and virtually?

- How can assessments be adapted so they are fair to both in-person and online learners?

Acknowledgements

The authors received an Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Sustainability Grant ($3,957) and a Garden Grant ($24,130) from The Paul R. MacPherson Institute for Leadership, Innovation and Excellence in Teaching, as well as an Echo360 Champion grant ($3,000) and EchoImpact Grant ($2,000) from Echo360 to support undergraduate student research.

References

Abdelmalak, M. (2014, March). Towards flexible learning for adult students: HyFlex design. In M. Searson & M. Ochoa (Eds.), Proceedings of SITE 2014–Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 706–712). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/130839/

Adeel, Z., Mladjenovic, S. M., Smith, S. J., Sahi, P., Dhand, A., Williams-Habibi, S., Brown, K., & Moisse, K. (2023). Student engagement tracks with success in-person and online in a hybrid-flexible course. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotlrcacea.2023.2.14482

Alsayed, R. A., & Althaqafi, A. S. A. (2022). Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Benefits and challenges for EFL students. International Education Studies, 15(3), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v15n3p122

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Beginnings: Where does hybrid-flexible come from?. In Hybrid-flexible course design: Implementing student-directed hybrid classes. Edtech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex/book_intro

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

CBC News. (2022, December 11). Union and McMaster University reach tentative agreement after 3-week teaching assistant strike. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/mcmaster-university-ta-strike-1.6682069

Crompton, H. (2013). A historical overview of mobile learning: Toward learner-centered education. In Z. L. Berge & L. Y. Muilenburg (Eds.), Handbook of mobile learning (pp. 3–14). Routledge.

Daymont, T., Blau, G., & Campbell, D. (2011). Deciding between traditional and online formats: Exploring the role of learning advantages, flexibility, and compensatory adaptation. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 12(2), 156–176.

De Bie, A., & Brown, K. (2017). Forward with FLEXibility: A teaching and learning resource on accessibility and inclusion (M. Brown & N. Mir, Illus.). McMaster University. https://pressbooks.pub/flexforward/

Groen, J. F., Quigley, B., & Herry, Y. (2016). Examining the use of lecture capture technology: Implications for teaching and learning. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and

Learning, 7(1), 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2016.1.8

Hoekstra, A. (2008). Vibrant student voices: Exploring effects of the use of clickers in large college courses. Learning, Media and Technology, 33(4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880802497081

Kohnke, L., & Moorhouse, B. L. (2021). Adopting HyFlex in higher education in response to COVID-19: Students’ perspectives. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 36(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2021.1906641

Lakhal, S., Khechine, H., & Pascot, D. (2014, October). Academic students’ satisfaction and learning outcomes in a HyFlex course: Do delivery modes matter? In T. Bastiaens (Ed.), Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning (pp. 1075–1083). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/148994/

Mamboleo, G., Meyer, L., Georgieva, Z., Curtis, R., Dong, S., & Stender, L. M. (2015). Students with disabilities’ self-report on perceptions toward disclosing disability and faculty’s willingness to provide accommodations. Rehabilitation Counselors and Educators Journal, 8(2), 8–19.

Matthews, K. E. (2018). Engaging students as participants and partners: An argument for partnership with students in higher education research on student success. International Journal of Chinese Education, 7(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340089

McCullough, K. (2022, August 15). ‘Can’t afford to focus on school’: Mac students return to Hamilton with soaring inflation, housing crisis. The Hamilton Spectator. https://www.thespec.com/news/hamilton-region/2022/08/15/mcmaster-inflation-housing-crisis.html

Mello, J. A. (2010). The good, the bad and the controversial: The practicalities and pitfalls of the grading of class participation. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 14(1).

Mercer-Mapstone, L. Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, K., Marquis, E., Shammas, R., & Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1) 15–37. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

Miller, J., Risser, M., & Griffiths, R. (2013). Student choice, instructor flexibility: Moving beyond the blended instructional model. Issues and Trends in Educational Technology, 1(1), 8–24. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/129818/

Miller-Young, J., & Yeo, M. (2015). Conceptualizing and communicating SoTL: A framework for the field. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 3(2), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.3.2.37

Omstead, J. (2022, November 7). 2,200 GO Transit workers on strike after failed contract talks, no bus service. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/9257860/go-transit-strike/

Polewski, L. (2018, April 14). McMaster and Mohawk closed due to potential ice storm—Hamilton. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/4144730/mcmaster-and-mohawk-closed-due-to-potential-ice-storm/

Paff, L. A. (2015). Does grading encourage participation? Evidence & implications. College Teaching, 63(4), 135–145. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24760624

Popov, O. (2009). Teachers’ and students’ experiences of simultaneous teaching in an international distance and on-campus master’s programme in engineering. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.669

Rogan, F., & San Miguel, C. (2013). Improving clinical communication of students with English as a second language (ESL) using online technology: A small scale evaluation study. Nurse Education in Practice, 13(5), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2012.12.003

Romero-Hall, E., & Ripine, C. (2021). Hybrid flexible instruction: Exploring faculty preparedness. Online Learning, 25(3), 289–312. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v25i3.2426

Shakil, I. (2022, November 4). Ontario schools shut as some 55,000 education workers strike in Canada. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/schools-shut-55000-education-workers-strike-canadas-ontario-2022-11-04/

Shingler, B. (2022, October 26). What to know about RSV, a virus surging among young children in Canada. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/rsv-canada-children-virus-1.6628778

Sowell, K., Saichaie, K., Bergman, J., & Applegate, E. (2019). High enrollment and HyFlex: The case for an alternative course model. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 30(2), 5–28.

Zerbini, G., & Merrow, M. (2017). Time to learn: How chronotype impacts education. PsyCh Journal, 6(4), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.178

Media Attributions

All images in this chapter have been created by the author, unless otherwise noted below.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.4. Long Description: The bar graph has the following approximate number of respondents for each flexible learning need:

- Commute: 120

- Time of day preference: 100

- Employment: 60

- ESL: 40

- Mental Health: 20

- SAS: 8

- Peer note taking: 6

- Other: 6

- Caregiving: 4

- Physical health: 2