4 Communicating our SoTL to Support Scholarly Teaching

Brett McCollum

Introduction

Why do SoTL scholars engage in the scholarship of teaching and learning? It can be to better understand our students and their experiences, or to explore the motivations and impacts of our practices. If SoTL is ultimately driven by a desire to improve student learning, then dissemination of our findings in appropriately public venues is a key component of good SoTL practice (Felten, 2013). Effective communication of scholarly inquiry into teaching and learning supports the practices of others – both their own scholarly inquiry and their teaching.

Scholarly Teaching with Educational Technology

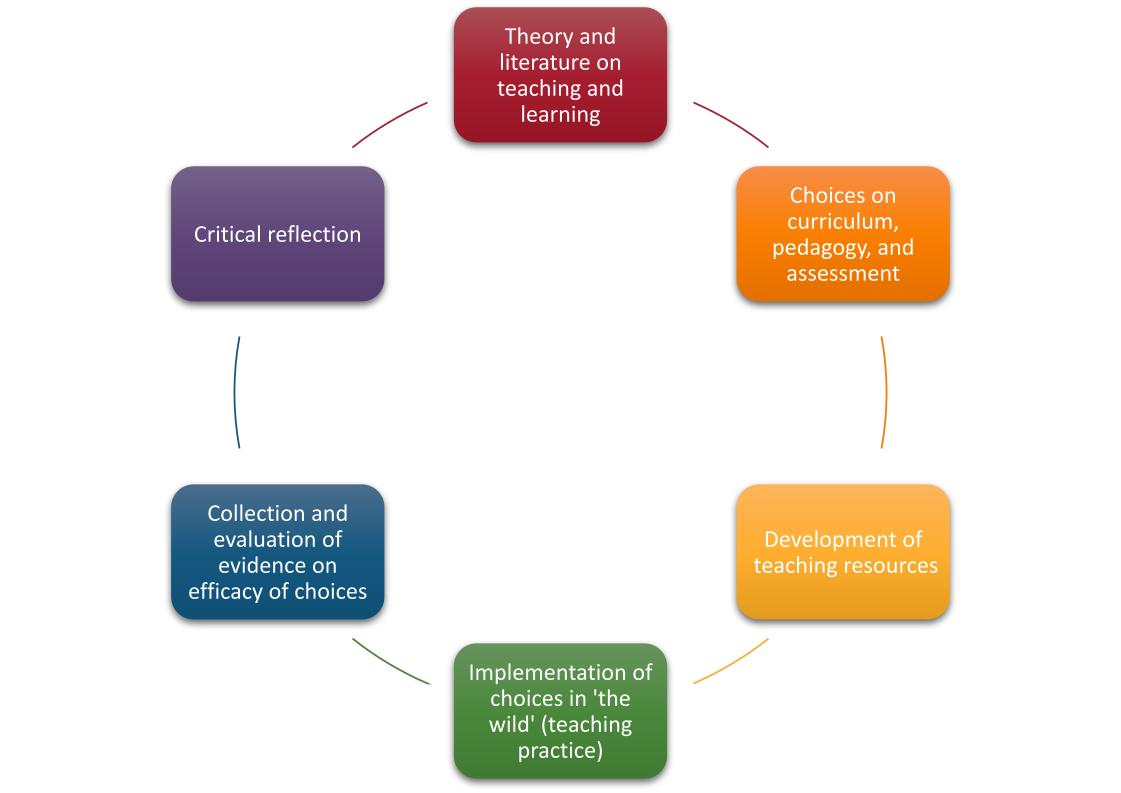

Scholarly teaching has been described through an overlapping magisterial model (Potter & Kustra, 2011). The process of scholarly teaching can be described as involving six steps, as shown in Figure 4.1. Scholarly teachers ground their practice in conceptually coherent, rational theory. They engage with relevant literature on teaching and learning, including SoTL and discipline-based educational research. Curricular, pedagogical, and assessment choices in scholarly teaching practice are then made based on theory with explicit connections to the literature. Teaching resources are created, curated, or refined with intentionality in alignment with the literature and founding theory. Scholarly teachers then experiment, implementing their resources and trialing their design choices within the wild (a.k.a. the classroom). Ethically appropriate methods are used to collect and evaluate evidence on the efficacy of curricular, pedagogical, and assessment choices. This evaluative process is conducted with a scholarly approach, including identifying your biases and basing your evaluation on evidence not anecdote. Scholarly teachers then critically reflect on the cohesion of the theory, literature, choices, and resources. They critically reflect on the appropriateness of their design for the course, its content, and its audience. They critically reflect on which of their professional skills they can improve to enhance the teaching and learning experience. Finally, the scholarly teacher begins the cycle again, using their critical reflections to guide their use of theory and literature. As educators continue to circumnavigate the scholarly teaching cycle, these research-informed choices shape their teaching identity, which is internally coherent in terms of beliefs, values, and behaviours.

Scholarly teaching with educational technology involves the same steps. Educators seeking to use educational technology in a scholarly teaching manner must familiarize themselves with conceptually coherent, rational theory such as m-Learning and social m-Learning (Koole, 2009; McCollum, 2016). They draw upon the literature to benefit from the knowledge and the experience of others. They make intentional curricular, pedagogical, and assessment choices that are informed by theory and literature. These choices include technological choices, and prompt important course design questions such as:

- What technology will be used, and why?

- Who will use the technology?

- When will the technology be used and for what purpose?

- How does the technology improve the teaching and/or learning experience, such as making the curriculum more accessible, enhancing the pedagogy, or improving the assessment process?

- What are the costs/impacts of including the technology in the course?

- What are the costs/impacts of not including the technology in the course?

- How will the technology alleviate issues of equity?

- How might the technology create new equity-barriers, and how will those be addressed?

- How might the technology impact the cognitive load of learners?

- Can the same learning objectives or student achievement be achieved without the technology?

- How will you evaluate the efficacy of your technological choices?

Scholarly teachers using educational technology then deploy the technology, collect and evaluate evidence on its efficacy, and engage in critically reflective practice to move from personal anecdote to evidence-informed practice (Cooper & Stowe, 2018).

Producing SoTL on Effective Uses of Educational Technology

While scholarly teaching does not require public dissemination, it does involve intentionality informed by established scholarship. As an academic field, the scholarship of teaching and learning creates and shares knowledge that advances our shared objective to improve learning experiences and environments. This often addresses issues of teaching or learning within disciplinary contexts, albeit with an effort to communicate value both within and beyond those disciplinary contexts (Weimer, 2008). In contrast, research questions that strongly emphasize disciplinary content and pose little value outside the disciplinary context are better classified as discipline-based educational research.

Trigwell suggests that “for the SoTL movement to be taken seriously, there needs to be a scholarly evidence-based practice associated with [its] purposes” (2013, p.96). Academic recognition for the field goes beyond valuing SoTL within tenure and promotion proceedings, as important as those are. It also impacts the willingness of others to read or listen to your findings, and to implement your scholarship within their own practice. For others to successfully use your SoTL findings, it is vital that your dissemination efforts be appropriately scholarly (Glassick et al., 1997), meaning that they should demonstrate:

- clear goals

- adequate preparation

- appropriate methods

- significant results

- effective presentation

- reflective critique

However, there is an important distinction between the aims of the scholarship of teaching and learning and those of most other academic fields. Unlike many esoteric areas of research that rarely have direct or immediate impacts on individuals outside of the field, the scholarship of teaching and learning often aims to directly support the scholarly teaching practice of our broad community of educators in post-secondary environments. These users of SoTL—educators within post-secondary institutions—are experts within their own academic fields. They are skilled evaluators of rigour and reliability in research within their areas of expertise. Yet, without adequate familiarity with the terminology, methodological approaches, theoretical assumptions, and scholarly foundation of a teaching and learning study, a reader may not attain the intellectual and emotional connection necessary to understand the work, appreciate its significance, or feel motivated to instigate change in their practice.

When disseminating SoTL on educational technology, your audience will be particularly interested in your technological choices and how the technology fits within your design. I refer the reader to the course design questions listed earlier in this chapter. Furthermore, your audience will be interested in the evidence of efficacy relative to the stated objectives of the inquiry, as well as your critical reflections on the alignment of the technology with your curriculum, pedagogy, and/or assessments. Clearly communicating your context will assist your audience in assessing what adaptations may be required for their own contexts. For example, a technological learning resource implemented within a small course section of affluent learners may not be feasible at another institution with large course sections and learners from varied socioeconomic backgrounds. Providing a generous set of supporting literature, woven together through a narrative of your scholarly approach to the problem of interest, can be an effective invitation for the audience to join you on your SoTL journey.

It’s Not Just About the Technology

While these considerations are important when disseminating all SoTL research we wanted to highlight them in relation to educational technology. When conducting a SoTL study that involves educational technology, it is important to align all aspects of the research to maintain a focus on teaching and learning. The technology fits within that context; in a SoTL project, it should not overshadow the ‘T&L’ of SoTL. This is not to say that there is no place for research that primarily emphasizes educational technology. Rather, such research is generally a poor fit for a SoTL journal.

In Section 3 of this book, readers will find examples of scholarly inquiry into the use of educational technology in teaching and learning within post-secondary contexts. Contributors make efforts to identify their choice of research paradigm, theoretical lens, and methodological approaches, and to justify the appropriateness of their choices. They explore the implications of their study for their own practice, and by extension, support the reader in considering potential benefits and consequences of adopting similar practices.

As you read the chapters in Section 3, we encourage you to reflect on the position of educational technology within each narrative. The scholarship of teaching and learning is inquiry into teaching and or learning. The technology is part of the context of the study. It may facilitate, support, extend, or enrich teaching or learning. However, the technology is not the purpose or focus of the study; that remains the participants in the teaching and learning experience. This emphasis is particularly important in the context of the rapid technological advancement our world continues to experience. The specific features of an educational technology may change even before a study is published, but the knowledge gained about teaching and learning is expected to have greater longevity.

We hope that, in your reading, you observe your attention being directed not to the specific technology choices of the researchers, but to the intentional design and implementation of their inquiry. Additionally, it is our hope that this book serves as an exemplar of how SoTL scholars should be explicit about their study’s design and assumptions, including epistemology, ontology, axiology, theoretical framework, and the motivation, development, and choice of their research questions. Being explicit in our writing supports practitioners and new SoTL scholars. It also helps us stay focused on our goal of improving student learning.

Disseminating SoTL to Scholars and Practitioners

In some ways, dissemination of the scholarship of teaching and learning has similarities to journalism. Adapting the work of Nelkin (1995) to SoTL dissemination, the role of publishing and presenting on SoTL for non-specialist audiences is to:

- Keep educators apprised of advancements in teaching and learning, often from positivist or humanist perspectives.

- Explain the appropriateness of a theoretical lens and methodological approaches for the study.

- Explicitly address the implications of the study for reflective and evidence-based teaching practices.

- Inform educators about choices relative to risks for themselves and their learners.

Keep in mind that there is potential risk to learners from stagnant pedagogy as much as from ineffective innovative practices.

Certainly, SoTL has additional roles in advancing the intellectual work of others in the field. The presence of numerous academic journals devoted to teaching and learning in and across the disciplines is evidence of this work. Yet, for scholars of teaching and learning to effectively support their disciplinary-research peers in improving teaching practices, we must keep the above roles of SoTL dissemination foremost in our minds during our dissemination activities.

The Scholarship of Abysmal Failures

Academics are well-aware that research often has unexpected twists and turns. Brave, enthusiastic, and adventurous educators pushing the boundaries of what has been done with educational technology have personal stories of abysmal failures. When studying the use of educational technology as a SoTL scholar, we should keep in mind that ‘negative’ results are still valuable. Dissemination of what you attempted, why, and how—with explicit references to design choices and underlying assumptions—and effective communication of what happened can fulfill a key role in the scholarship of teaching and learning, particularly in relation to the practices of non-specialists. Namely, it can inform educators about the consequences of particular choices, helping them avoid unnecessary risk for themselves and their learners should they choose to explore similar teaching and learning strategies involving educational technology.

Asking and Posing Questions

I pose the following series of questions for the reader to consider as they engage with this book. We, the editors of this book, also encourage you to use these questions as you develop your own SoTL studies related to educational technology:

- What aspect of teaching and/or learning is the investigator seeking to affect with educational technology?

- With which genre of SoTL does the study best align? (Example: Inquiry)

- What paradigm, philosophical belief, theoretical approach, and associated assumptions is the investigator using in their study?

- How do these design choices influence the findings and/or interpretations of the study?

- Are non-SoTL experts in higher education among the author’s intended audience? If so, how does the author communicate their study to support the scholarly teaching of this audience?

- Which findings are intended to support adoption of similar practices, and which are presented as advice to avoid unnecessary risk?

You may also wish to reflect on the following questions as you read:

- How do you currently determine if a particular approach to using educational technology leads to effective learning?

- Are your methods or metrics for analyzing the use and impact of educational technology appropriate, and do they include inclusive and equitable lenses?

- Does your inquiry into educational technology tend to focus on cost, benefit, barrier, or opportunity in teaching and learning?

- How can you more effectively communicate your scholarship on teaching and learning to support both scholars and practitioners?

Finally, we challenge you to reframe each of the following research questions to shift their focus away from the educational technology itself and instead toward the related teaching and/or learning goals.

| Research Questions Focused on Educational Technology | SoTL Research Questions Focused on a Context Involving Educational Technology |

|---|---|

| Which design features are available in social media platforms for professional development? | |

| What analytics are available in different learning management systems? | |

| What interactive features can be embedded within online instructional videos? | |

| In a course gamification app, how does the artificial intelligence make decisions to replicate a real player? | |

| How can statistical syntax and introductory concepts be represented in R, SPSS, and MATLAB? |

References

Cooper, M. M., & Stowe, R. L. (2018). Chemistry education research—From personal empiricism to evidence, theory, and informed practice. Chemical Reviews, 118(12), 6053–6087. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00020

Felten, P. (2013). Principles of good practice in SoTL. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 1(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.2979/teachlearninqu.1.1.121

Koole, M. L. (2009). A model for framing mobile learning. In M. Ally (Ed.), Mobile learning: Transforming the delivery of education and training (pp. 25–47). Athabasca University Press.

McCollum, B. (2016). Situated science learning for higher level learning with mobile devices. In Kennepohl, D. (Ed.), Teaching science online: Practical guidance for effective instruction and lab work. Stylus Publishing. https://sty.presswarehouse.com/books/BookDetail.aspx?productID=393126

Nelkin, D. (1995). Selling science: How the press covers science and technology. W. H. Freeman.

Potter, M. K., & Kustra, E. (2011). The relationship between scholarly teaching and SoTL: Models, distinctions, and clarifications. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(1), Article 23. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050123

Trigwell, K. (2013). Evidence of the impact of scholarship of teaching and learning purposes. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 1(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.1.1.95

Weimer, M. (2008). Positioning scholarly work on teaching and learning. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2008.020104

Media Attributions

All images in this chapter have been created by the author, unless otherwise noted below.

Long Descriptions

Figure 4.1 Long Description: A circular diagram showing the cyclic process of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) with six connected steps: [clockwise from top]

- Theory and literature on teaching and learning

- Choices on curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment

- Development of teaching resources

- Implementation in practice

- Collection and evaluation of evidence

- Critical reflection, which loops back to the first step